Dear Friend,

How do we expand our love so that it’s not only our children or immediate family and friends whom we cherish, but all people? This is the question that ends the first part of The Book of Joy, and what the editor, Douglas Abrams, means by “the elasticity of love.”

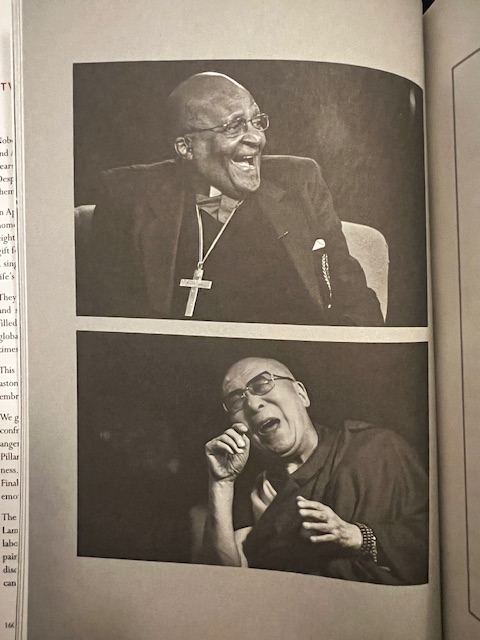

He raises the question after a full day talking about joy with His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, both of whom are shown to be joyful, loving, and affectionate people, despite their difficult backgrounds.

The Dalai Lama was exiled as a child and forced to leave his home, all the while taking on the immense responsibility of leading the people of Tibet and of being the living embodiment of the Boddhisattva of Compassion–one of the awakened, and a worldwide religious leader for Tibetan and other Buddhists. Archbishop Tutu lived through South African apartheid and became one of the major forces for its elimination, as well as a leader of the nation’s reconstruction after the end of the apartheid government. He has battled cancer and was indeed battling it during their visit. Still, these two spent their first day laughing and joking, hugging and holding hands, and seriously praising the power of love.

In other words, although the men are leaders of different faiths, although they both have experienced (or suffered) great difficulty in their personal lives, and although they sometimes disagree on how much control a person has over the experience of pain and suffering, they each agree that being more loving, more generous, and more joyous is just about the only thing that actually makes the world, and our own lives, better. This is something I’ve also come to believe in recent years.

What’s been interesting about the read so far is that the editor is also involved in the conversation. I had read a few reviews of the book prior to starting my journey with it, so I knew this was going to happen and that many people had complained that they found his participation distracting or disappointing. So far, I feel quite the opposite. While the Dalai Lama and Archbishop base many of their responses off of their faith and lived experiences, Abrams adds to these studies the sciences and psychology that seem to confirm their beliefs about the power of love and joy, compassion and gratitude. To me, this is significant, and I think the Dalai Lama, as a person deeply interested in science himself, would agree.

One example of this comes in the segment title, “Nothing Beautiful Comes Without Suffering.” There’s a difference, says the Dalai Lama, between foolish selfishness and wise selfishness. Foolish selfishness would be the drive to do only things that make you happy simply because they make you happy, without any regard to how these actions affect others. Wise selfishness would be doing things that make you happy because they make others happy, thereby extending that circle of happy and creating positive effects rather than neutral or negative ones. Abrams steps in after the leaders’ conversation about this to describe a psychological study that supports the idea of wise selfishness. He writes that recent studies suggest about half of our happiness is a result of determined factors, like genetics or personality, while the other is determined by both circumstances (limited control) and response to circumstances (great control). Out of all possible factors, the three that have the greatest influence on increasing our happiness are “the ability to reframe our situation more positively, our ability to experience gratitude, and our choice to be kind and generous.”

Each of those three factors has something outward-looking to it. We can reframe our situation by having compassion for the situations of others and by empathizing with their circumstances; we can brighten another’s day by expressing how and why we are grateful to them or for them; and we can literally take positive action by acting and speaking skillfully, and being more giving, with the people we encounter each day.

Ultimately, while we might do these things to be happier ourselves, they will also create the conditions for improving the happiness of others in our orbits. The idea is, if we are creating happiness in others, they’re more likely, too, to spread happiness and to be positive, which will continue on, and eventually this makes its way outward in greater circles, and back to us.

I marked so much in these first eighty pages that I could probably write an entire series of reflections on this “Day 1,” but I’ll highlight just one other part of their conversation that I found personally affecting. It comes in the section titled, “Have You Renounced Pleasure?” After some discussion about the nature of pleasure and what joyful pleasure is versus the pleasure of self-satisfaction (the pleasure that changes our spirits rather than the kind related only to momentary gratification), Abrams returns to scientific study, this time on hedonism. He explains hedonism by referring to the tale of Gilgamesh and the deity Siduri, who claims that the concerns of humanity are, essentially, frivolity. According to Abrams, “in many ways, hedonism is the default philosophy of most people and certainly has become the dominant view of consumer ‘shop till you drop’ culture.”

What’s the explanation for this? Well, I think it’s the confusion about how to be happy. We all, I imagine, know that we’re supposed to be happy. And we want to be happy. And we want others to be happy. But when we become so focused on that question without knowing how to do this, or why it’s really important, we can get wrapped up in instant gratification, consumerism, and addiction. I know that in my hunt for happiness, I’ve certainly fallen prey to all these things. Yet, as Abrams notes, “scientists have found that the more we experience any pleasure, the more we become numb to its effects and take its pleasures for granted.” So, there’s a difference between joy and pleasure. This isn’t to say that pleasure is bad, but instead, to be grateful for a moment of pleasure when it arises, without becoming attached to it and constantly seeking its repetition as a means for happiness.

Happiness is something else entirely. Joy is deeper than the drink, brighter than the casino lights, louder than the favorite song, and warmer than the lover’s body. And the experience of joy can be cultivated as a daily practice, a way of being, so that searching for it becomes unnecessary. In this way, the pitfalls of a pleasure-seeking are toothless.

Meditation: “Just as water seeks its own level, the mind will gravitate toward the holy. Muddy water will become clear if allowed to stand undisturbed, and so too will the mind become clear if it is allowed to be still.” -Deng Ming-Dao

Joyfully,

~Adam

Leave a comment