Dear Friend,

Mother tongue. Mother land. Mothers and daughters.

The first chapter of the three we read this week is “Calliope,” the Muse of epic poetry. And this epic is a snapshot of both Cha’s mother, Hyung Soon Huo, and their motherland, Korea. The entire chapter, and this relationship to mothers of all kinds, seems best summed up in a phrase Cha use, Mah-Uhm. She writes:

“It is the mark. The mark of belonging. Mark of cause. Mark of retrieval. By birth. By death. By blood. You carry the mark in your chest, in your MAH-UHM, in your MAH-UHM, in your spirit heart. You sing.”

This term is a new one to me, but how it speaks to me! I’m reminded of the Japanese ikigai, which is a term for motivating purpose, for meaning. In this case, though, Mah-Uhm seems to reflect something that is both historical and psychological, and communal. Where ikigai is one’s purpose and meaning in life, connected to their intentions each day, Mah-Uhm is more like, essence, and its intimately connected to language, which Cha returns to again when she tells us that her mother’s language is forbidden in China, where she’s moved to avoid the Japanese occupation of Korea.

Part of this epic poem, them, is Odyssean, a hero prevented from going home.

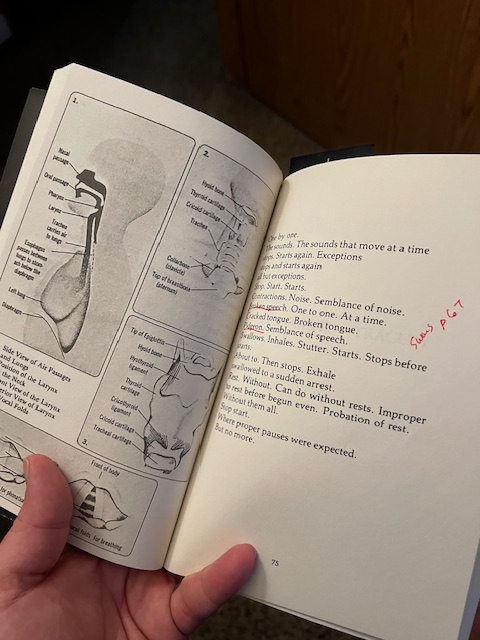

The next sections, “Urania” and “Melpomene,” are equally powerful. “Urania” is the Muse of Astronomy, but this chapter focuses entirely on language and translation. It’s a beautiful poem whose reoccurring tropes include engagements with language concepts as specific as verb tense and as general as metaphor. To me, it’s equally as engaging to read her musings on the literal mechanics of language construction, in the throat and mouth, as it is to read the more romantic parts of her exploration, as when she writes, “I heard the swans / in the rain I heard / . . . / Rain dreamed from sounds.”

Finally, in the chapter on tragedy, Cha returns to herself, the thoughts on the war, and begins with a letter to her mother, where she reflects again on the loss of language. (“I speak in another tongue now . . . a foreign tongue.”) She reminds us that even though the Japanese were defeated during World War II, Korea has been “severed in two by an invisible enemy under the title of liberators.” So, the fight for independence in the 1960s continues, and it is led again by the youth, by the students, just as it was a half-century before. Cha loses her brother to that fight.

“You fell. You died you gave your life. That day. It rained. It rained for several days. It rained more and more times.” For Cha, the loss and the victory, both, are in the rain. The rain that saturates the ground of Korea, that “does not erase” afterwards, but that also nourishes the future. It is a bittersweet victory for Cha and Korea, and a bittersweet antithesis between the damaging and seemingly unpreventable floods of war and liberty, with the waters of life.

When I first scanned Dictee and read brief descriptions about it, I was a bit confused, even nervous, about how this piece would hold together, but now that we’re halfway through the book, I begin to understand how each of these chapters and their distinct focuses come together to tell the same story, and how they relate to the Muses Cha invokes. It’s a breathtaking reimagining not only of a life, but of a time and a people.

Meditation

“There is no destination other than towards.” -Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

May you be happy and at peace,

~Adam

Leave a comment