Dear Friends,

“West is the direction of endings . . . [i]t represents learning to find the road in the darkness” (109).

If you’re paying attention the cover pages for each chapter, you’ve probably figured out by now that they do a nice job of summarizing the theme or mood of what’s to come.

In the last chapter, “North,” Harjo alludes to difficulty and prophecy. It was a clever summary. That phase of Harjo’s life was indeed filled with difficulties and disappointments, but it also revealed to her, I think, a lot of her talents and abilities, desires and possibilities. While it wasn’t a cheerful stretch of time by any means, it seemed to have at least been filled with important and useful lessons.

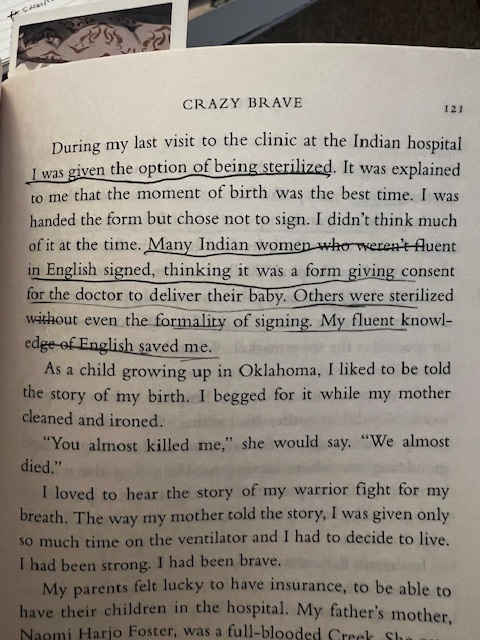

“West,” though, sits in that promised darkness. Teenage Harjo begins this phase with some lingering hope for her life and future with the boy–father to her child–who has all but abandoned her. And she does reunite with him, though the costs seem hardly worth it. She is beset with problems from the time she leaves her parents’ house to join her boyfriend. Her new mother-in-law is jealous and interfering. The hospital where she gives birth nearly forces her into being sterilized. She writes that it’s her “fluent knowledge of English” that saved her, because so many other indigenous women who couldn’t read or understand English were sterilized without their consent or knowledge (121).

In this way, Harjo’s life experiences are again personal and political. They reveal so much about who we are as a nation, where we’ve been and what we’ve done to each other. This first-hand account provides important nuances to larger societal issues, like racism. As Harjo notes, prejudices about color abound, even within non-white marginalized groups. Her mother-in-law, for example, thinks Harjo must come from a wealthy family “because [her mother] was a lighter skinned Cherokee who passed for white” (120). These are insights that can only come from primary experience, and though they make the reading painful at times, the accounts also make the reading important.

Something that stands out to me, then, is that while this is clearly Harjo’s individual experience, a lot of what she lives through is relevant and relatable to so many of us. I think I found these last two sections hard to read because I knew where she was coming from. Now, I’ve never had a mother-in-law who practiced witchcraft and often tried to curse me, nor a lover who had children by three different women, none of whom could he support. But when she writes about being different, about suffering prejudice and surviving poverty, about the constant call to leave and be left, the ceaseless stepping forward into nothing, that spoke to me. I think it speaks to a lot of us who have felt stuck, even trapped, by our circumstances and who wonder why we keep going, how we’ll ever get out of it, whether we should even keep trying. Depending on the state one’s in when reading about this part of Harjo’s life, it could be easy to sink into despair.

It helps that Harjo never despairs herself, never stops believing in her “knowing,” and it certainly helps to know that, eventually, this lost and lonely woman would eventually become Poet Laureate of the United States.

It will be curious, and a little exciting, to learn how she got there.

Meditation

“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers / That perches in the soul / And sings the tune without the words / And never stops – at all – ” -Emily Dickinson

May you be courageous,

~Adam

Leave a comment