Dear Friend,

As I write this response, it’s a quiet Saturday morning, early before everyone wakes. As I sit by myself listening to Sufjan Stevens’s Seven Swans spinning on the turntable, I realize this early quiet is my favorite time of day. And it’s perfect for contemplation.

It’s times like these that let me see my own notes a little differently. It’s exciting what we can discover even after thinking we’ve read something slowly and deliberately. These chapters of The Prophet are so short, it’s hard to imagine I could miss anything, and yet, when I picked up the book again this morning to go through my notes and annotations, I realized I had missed two things that now seem glaringly obvious.

The first thing I missed was that there’s no need for chapters, because Gibran puts the chapter’s theme, what would be the title, according to the book’s table of contents, in the first sentence of every section. If you read my post last week, you’ll have seen that I was hand-writing the chapter titles into the blank space at the start of each. There wasn’t any reason for this beyond trying to keep my own place in the reading.

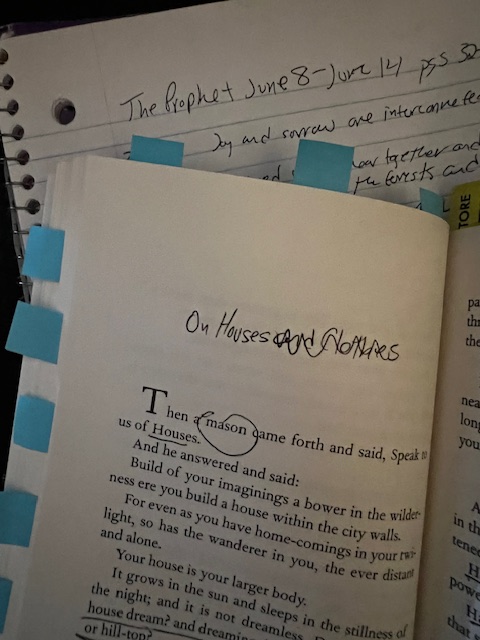

Imagine my surprise, then, when I started to write the title of chapter eight, “On Houses,” only to see it there in the first sentence! I went back to every chapter read last week and, sure enough, there they all were. It suffices to say, I stopped writing the chapter titles at that point and started simply underlining the theme word (or words) in the first sentence of each.

That wasn’t the only obvious miss, though. About halfway through this week’s reading, I realized there was something else in the first sentence that was obviously intentional, which is the type of person asking the prophet their question. Each chapter is an idea prompted by an individual present at the prophet’s leave-taking. Why didn’t it occur to me to think about who was asking the questions each time, even though it is clearly stated? It only caught my attention a few chapters into this week’s reading, when I realized the person asking about “buying and selling” was identified as “a merchant.” So, who asks each question so far?

- Almitra (the Seeress identified in the first chapter, and the only person recognized by name thus far) asks about love.

- Almitra asks about marriage.

- A woman asks about children.

- A rich man asks about giving.

- An innkeeper asks about eating and drinking.

- A ploughman asks about work.

- A woman asks about joy and sorrow.

- A mason asks about houses.

- A weaver asks about clothes.

- A merchant asks about buying and selling.

- The judges ask about crime and punishment.

- A lawyer asks about laws.

- An orator asks about freedom.

A few things about this list are worth considering. First, the simple who for each question. Most of these interrogators make sense, as they’re asking about what they know or what they do. The lawyer and his laws, the ploughman and his work. But it makes me think about perspective and about wonder. About curiosity. It might be natural to ask about what we know, but where are the ones asking about what they don’t know? I find the quest for spiritual or philosophical depth in one’s purpose meaningful, indeed, but also fascinating to me is to wonder about that which hasn’t been experienced by the self.

I’m also curious about some of the generality or specificity in the questioning. For example, we get certain particulars about most people doing the questioning. “A weaver” and a “ploughman” ask about their work. But twice, it’s “a woman” asking about children, first, and then about joy. It seemed to me at first that there was a clear distinction between men’s labor and women’s’. The men are attached to specific jobs, whereas the women–jobless–ask questions of a more conceptual nature. Of course, this means I am assuming that the weaver and the mason and the judge are all men, which is admittedly problematic, except there’s not much explanation, otherwise, for why the two women would be identified only as “a woman,” if not to contrast them with the individual laborers, who are likely men.

The last part of this week’s reading that moved me deeply was the prophet’s commentary on nationalism. When the orator asks about freedom, the prophet is careful to explain that freedom taken to the extremes of a prideful nationalism becomes slavery. “I have seen the freest among you wear their freedom as a yoke and a handcuff,” he says (50). Everything exists in balance. There is nothing good or light or lovely without the bad, the dark, and the harmful. So, too, are the people responsible for the tyrant. “How can a tyrant rule the free and the proud but for a tyranny in their own freedom and a shame in their own pride?” (51). The people must take care with their language of freedom to make sure they’re not blinding themselves to what it really means to be free.

Meditation

“You are the way and the wayfarers. And when one of you falls down, he falls for those behind him, a caution against the stumbling stone. Ay, and he falls for those ahead of him, who though faster and surer of foot, yet removed not the stumbling stone.” -Kahlil Gibran

May you be free,

~Adam

Leave a comment