Dear Friend,

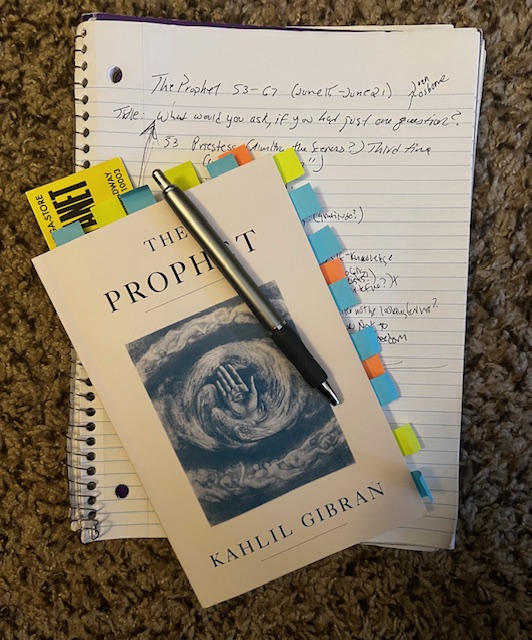

Friendship. Freedom. The quest for knowledge. These are the primary themes in this very short section of seven chapters, in which the priestess returns to ask a third question, another vague “woman” speaks up for the third time (on pain), and a general “man” asks about self-knowledge.

And that’s the question that stands out most to me, along with the teacher’s question about teaching. In pursuing these thoughts, the prophet suggests that knowledge must be found on one’s own, and that there are many truths. He equates “self-knowledge” specifically to the soul but is cautious to remind his listeners that the quest really shouldn’t be for one answer, or even of one soul, but instead “a truth.” As he puts it, “the soul walks upon all paths [and] unfolds itself, like a lotus of countless petals” (59). The constant of life is that it changes. “I am large,” wrote Whitman. “I contain multitudes.”

He also suggests, “no man can reveal to you aught but that which already lies half asleep in the dawning of your knowledge . . . if [the teacher] is indeed wise he does not bid you enter the house of his wisdom, but rather leads you to the threshold of your own mind” (60). In other words, to be taught and to find self-knowledge, there must at least be a willingness to learn and to accept something different from what you’ve always thought or known. This reminds me of a song by The Belle Brigade, “Where Not to Look for Freedom,” in which the band sings, “I’ve been looking real hard for a teacher / but they better not be looking for me / ‘Cause I never found one in a preacher / anyone that says they see what I should be.”

So, what does that mean? Well, to me, it seems a healthy reminder that many truths are relative and temporal, and that the soul is an ever-changing thing. Truths and the soul are personal and universal. They change as we change, and yet they persist in all things. One truth I’ve discovered is that all beings, all things, are interconnected, yet it’s also true that we see things from our own perspective and based on our own experience. We can’t really be forced to learn, or to change, but we can keep ourselves open to every experience and then decide for ourselves what is true to us–or nature, our identity, our soul–however we understand it.

Which raises another important question, which I’ve framed after Joan Osborne’s song, “One of Us?” In that song she asks, “what would you ask [God] if you had just one question?” I was reminded of this lyric after the third appearance of Almitra, the prophetess. In the first chapter of this section, Almitra asks about Reason and Passion. The prophet goes on to explain, again, that all things exist in a balance. We need both reason and passion, but we must be careful to not to be swayed completely by one or the other. “God rests in reason [and] God moves in passion,” the prophet explains.

And so, I began to wonder, what would I ask–of god, or a prophet, or a respected teacher–if I had the opportunity? If, like the townspeople who have gathered to bid farewell to their prophet and to ask him to share his wisdom one last time before he goes, I was given the chance to learn anything at all, what would I want to learn? Or need to know? It’s such a strange concept to consider, and it reminds me of my reflections last week, when I pondered why each of these people asked only about their own experiences. Would my question be of the more conceptual type–something “grand”? Or would I too ask something that mattered only to me in the moment, as in the virtue of my own work? One wants to imagine they would ask the big questions, but who’s to say?

If I imagine the moment and picture the teacher I’d most like to hear from, I suppose I’d ask about softness and poetry.

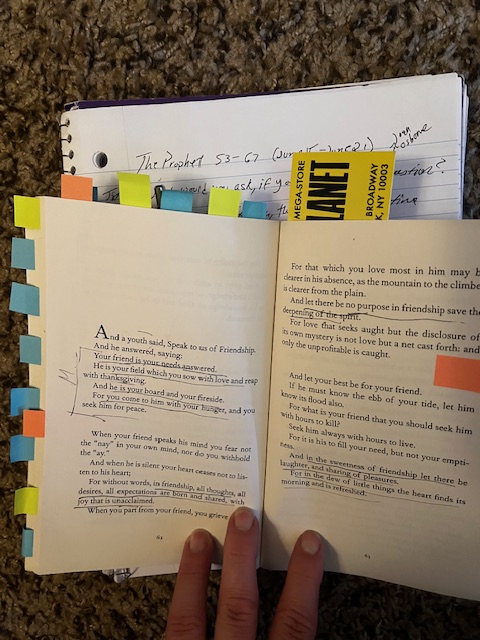

My favorite part of this section might be my favorite part of the book so far, which is the youth’s question on friendship. “Your friend is your needs answered,” says the prophet. “He is your field which you sow with love and reap with thanksgiving. And he is your board and your fireside. For you come to him with your hunger, and you seek him for peace” (62).

Reap with thanksgiving. It’s wonderful to return to this concept of gratitude, because earlier in the book, the prophet seems rather cautionary about living a life of gratitude. Here, though, it seems quite clear that there are some things for which we should be thankful, and I couldn’t agree more that a good friend is at the top of this list.

“Let there be no purpose in friendship save the deepening of the spirit . . . and in the sweetness of friendship, let there be laughter, and sharing of pleasures. For in the dew of little things the heart finds its morning and is refreshed” (63). It’s no exaggeration that the blessing of good friendships has guided me through darkness and that these friendships have shaped the person I am today.

Friendship is one of the truths of my soul, the presence of which has stayed constant, though its nature changes.

Meditation

“I went to the doctor, I went to the mountains / I looked to the children, I drank from the fountains / There’s more than one answer to these questions / Pointing me in a crooked line / And the less I seek my source from some definitive / The closer I am to fine.” -Indigo Girls

In loving friendship,

~Adam

Leave a comment