Dear Friend,

“Response is my strategy. Endless responses.”

Shocking Statistics

I spend a lot of time talking with my students about the three rhetorical appeals for argumentation, ethos (credibility/authority), pathos (emotion), and logos (logic). It’s especially important to consider the use of these three in relation to your audience and your purpose, or what we’d call the rhetorical situation. With a text like Just Us, which is making an argument that many audiences will be sensitive to and about, I think it’s important to argue with a balance of all three appeals, especially if Rankine expects that people who aren’t necessarily in full agreement with her will be reading the book. (We can get away with a lot of emotion if we know our audience is already sympathetic, for example, but if we’re not careful, those sorts of appeals can turn off the audience we most need to reach.)

This is why I was particularly appreciative of the statistics Rankine presented near the start of this week’s reading, in “boys will be boys,” and then again in “complicit freedoms.” After many chapters of personal anecdote and emotional appeal, it was important to see some numerical evidence to help illustrate the personal experiences she’s been writing about. For example, she explains that in the 2015-2016 school year, a shocking 81% of American public-school teachers were white, and that the most recent data suggests that 76% of full-time faculty are white. I often hear resistance to these statistics, as if it doesn’t matter who is at the front of the class, but the truth is, it does matter. When we see positive role models who look like us, it can be life changing. A lifetime spent without these leads one to believe that there is no path for us, that there are jobs, spaces, and relationships not available to us. So, what might it mean for a young person of color to go through their entire twelve-year educational experience perhaps never having seen a teacher who looks like them?

Not Just an American Problem

Later, Rankine does a similar investigation, but this time with research into blond hair and its relationship to power. She presents a compelling and disturbing argument that blond women seem to have more professional success, and that spouses with blond wives also seem to have more success in their own careers. This is explained in direct relation to the trend of Black and Asian women who dye all or part of their hair blond, and it’s later re-evaluated through conversations on skin lightening and colorism. Whiteness in all things, it seems, can be correlated, at least psychologically, and through psychology, experientially, with power.

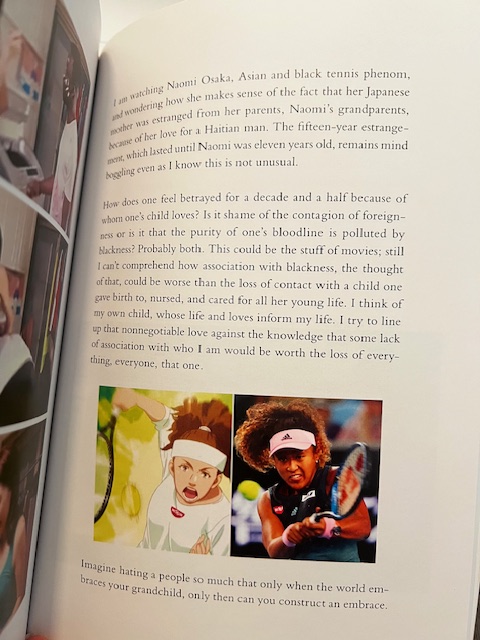

Perhaps the most striking example in the book of this kind of colorism, or color racism, is of Naomi Osaka, an “Asian and black tennis phenom.” Rankine notes that in illustrations, her skin color is lightened, and that online and in news reporting, she’s often referred to in derogatory terms, sometimes even by the cultural equivalent of the “N word” in the United States. It’s a powerful example, given how popular and successful Osaka is, and a reminder that if even the most beloved and respected public figures can experience such culturally condoned racism, what is the average person likely to deal with in their day-to-day life?

Check and Reflect

Something Rankine does throughout the book is provide notes and citations for her work. Sometimes it’s a reference to where she heard, saw, or read a particular term that she uses in context, but which is not her own. Other times, it’s citations for data from which she’s drawn a conclusion or made a particular argument, as in “jose marti,” where she writes about assimilation and Indigenous communities, and provides the source and summary for a book she’d consulted and for United States census data that informed her claim.

All of this is the kind of logos (logic in evidence) that I wrote about above as being so important to the rhetorical strength of an argument, but she goes even further by offering appeals to her own credibility throughout as well. I think she does this well when she reflects on her interactions with others, whether it’s commentary during or after a conversation, or in response to a written correspondence she’s carried on with a friend or colleague. Rankine often writes about how she sent portions of the book to friends, for example, and includes both their reactions to her work as well as her reactions to their responses. It’s a kind of self-reflection and evaluation that’s important to presenting oneself as credible, thoughtful, and open.

I think my favorite type of this reflection that happens throughout, is when she fact checks her own work. As I mentioned, she’ll often include notes and sources for her claims, but she sometimes also includes a “fact check,” and these fact checks are sometimes correctives. In “liminal spaces ii,” she incorporates an anecdote about Eartha Kitt and then-First Lady Johnson, which she fact checks on the adjoining page: “No. This may be true, but both sides allegedly later deny that she actually cried” (218). It’s an interesting strategy, to leave the original claim or explanation in place, but correct it, rather than to fix the claim in-text during editing. Personally, I think it’s remarkably instructive, an example of critical thinking in action and a reminder to readers that we, too, can modify our beliefs or interpretations when presented with new evidence.

Thank you for reading Just Us: An American Conversation with me this month. It was a challenging book, both in its form and content, and one that I know leaves some readers wondering about Rankine’s purpose. Fortunately, she clears that up in the final pages, when she reminds us that her purpose is always to respond. It’s an invitation to us to carry on the conversation, no matter how long it lasts or how difficult it gets.

I hope you’ll join me tomorrow for the introduction to our next read, Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI by Ethan Mollick. Thank you for a wonderful first year at the Contemplative Reading Project. See you in Year Two!

Meditation

“If you close your mind in judgments and traffic with desires, your heart will be troubled. If you keep your mind from judging and aren’t led by the senses, your heart will find peace.” -Lao Tzu

May you be at ease,

~Adam

Leave a comment