Dear Friend,

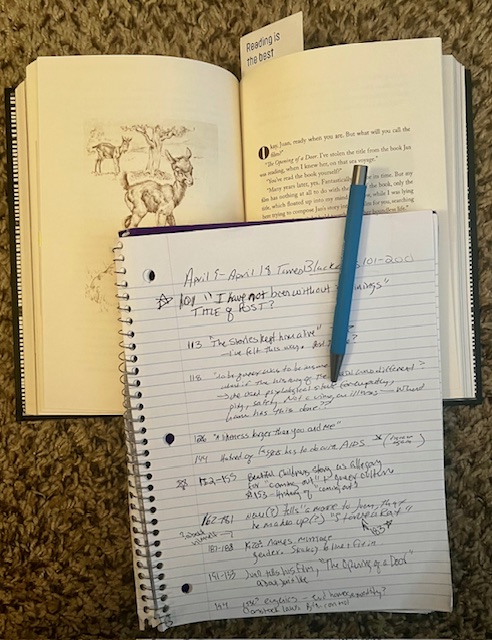

When the narrator writes of Juan, “the stories kept him alive” (113), I had to stop and catch my breath. I, too, have felt that way. I suppose part of this very project–reading slowly and carefully together–is an attempt not just to stay alive, but to be alive. And it isn’t just that Juan is kept alive by hearing the wicked stories from our narrator’s life, it makes him want to keep living.

There’s such a difference between being kept alive and being alive, isn’t there? Between staying and wanting to stay. Stories are one of the ways we make life more enjoyable, more knowable, and more tolerable. As James Baldwin said, “you think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”

So, to read is to find community. Sometimes we find it there in the pages of the book we’re reading. Sometimes we’re able to create it around the act of reading, with projects like this one. But connection is the point: connection to our self, our communities, our friends and neighbors. To our ancestors and our progeny.

Community is also paramount to the survival of marginalized and minority groups, like lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. A principal topic in the study of LGBTQ+ history is the communities that developed all over the world, across all time periods, to foster the joy and safety of these people. When Juan tells the narrator that there’s “a likeness larger than you and me,” I think he’s talking about the sense of self we see in others who are like us in those unique, often misunderstood, ways. This likeness is crucial to establishing communities where we feel safe, loved, and supported, and where we can learn to thrive through mentorship of elders who have experienced what we have, and who survived it.

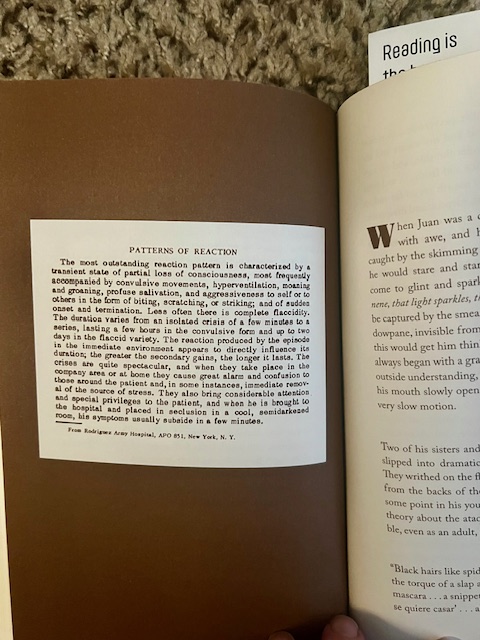

That’s especially true for communities like LGBTQ+ ones. There’s a lot of focus on disease in this section of the book, both mental and physical ailments. In the history of LGBTQ+ acceptance, there was a time in the late-1800s when it was considered a great win for homosexuality to be decriminalized on the basis of same-sex attraction being considered a mental illness rather than a crime. In some ways, that was perhaps a necessary step in the march for progress. In other ways, it encouraged a different kind of prejudice against LGBTQ+ people, one which, when the HIV/AIDS outbreaks began, quickly morphed into the adoption of homosexuality as a physical and catching disease, not just a mental illness.

It makes so much sense, then, that these chapters include some new features. The first is the addition of excerpts from academic articles, covering medicine, psychology, and the sciences. Much like the blacked-out sexology book, these excerpts help to connect the personal, public, and institutional spheres and to reinforce the fact that identity is constructed through all sorts of methods, including the personal, the social, the religious, and the scientific, among others.

Another new feature is the intensive focus on storytelling. In these one hundred pages, the narrator tells one of his stories, which he’s apparently done for Juan on many occasions. Juan then reciprocates with a story of his own (which goes on much longer, so in fact we’re not done with it, yet). Both stories, though, mix elements of biography with fiction, and both are again methods of responding to and building community, of creating bonds, of seeing and being seen. These stories are supported by the beautiful children’s books written and illustrated by another character who is not present but often mentioned, and they cover topics like “coming out” in such tender and natural ways.

There’s so much more to write and think about in these hundred pages, from the same-sex marriages that were happening as far back as the 1920s (and even much earlier), to eugenics and its relationship to birth control, Planned Parenthood, and homosexuality, to the history of coming out as a class and social function, and how it was adopted by and adapted for queer people. Blackouts is turning out to be a network of stories, covering every imaginable aspect of human existence, and this might turn out to be the very point, and great triumph, of the novel.

Meditation

“When another person makes you suffer, it is because he suffers deeply within himself, and his suffering is spilling over. He does not need punishment; he needs help. That’s the message he is sending.” -Thich Nhat Hanh

In loving kindness,

~Adam

Leave a comment